I was first alerted to the work of Irving Biederman, professor of neuroscience at USC, via this WSJ article on the nature of addictive websites. I’ve been a fan since. His experiments are fascinating, probing everything from the neural basis of shape recognition—with members of remote African tribes with no exposure to uniform, manufactured objects as test subjects—to whether or not people are able to recognize faces in the form of pigmented “3D blobs” that look like teeth. But his work on the evolutionary factors behind scene preference is of special interest to web people. Biederman found test subjects preferred scenes like this,

Over scenes like this:

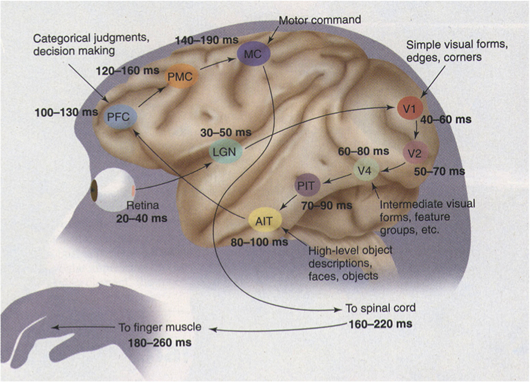

And more than that, preferred scenes were accompanied by high levels of neural activity in the association areas of the brain. Greater neural activity increases production of opioid neurotransmitters; the greater the rate of opioid release, the more pleasurable the experience. The association areas of the brain have a high density of opioid receptors—neural activity there is pleasurable, and addictive.

The big pile of bricks above is what Biederman calls an “uninterpretable input.” It’s a random-appearing mass. “Novel inputs” like the garden scene above result in extensive interpretation and association and release a pleasurable flood of opioid hits. Repetition of novel inputs though result in rapidly diminishing opioid returns.

What makes a scene richly interpretable from an evolutionary perspective? Well: mystery (“How likely is it that something new might happen or that you would obtain different information from changes in your vantage point?”), vista (“How extensive is the view? Good reconnaissance?”), refuge (“Is there a position in the scene where you can achieve a good vantage point without being seen?”) and whether the scene is natural or urban (“Does it afford food or water?”).

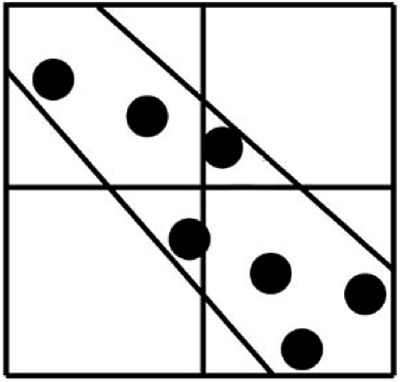

To illustrate that pleasure is generated in that moment of novel interpretation, Biederman turns to Droodles. Droodles are doodle-riddles.

Have a look at this droodle:

Then have a look at it again with a caption:

Better, right? Biederman opted not to use lolcats in his study.

We’re forever seeking new and richly interpretable information. It’s how you got here. Addictive web apps offer a constant stream of new information ripe for interpretation and association. Nowadays, with our needs for survival met, we spend much of our waking lives attempting to satisfy this drive. Some of us have learned that the internet is a great place to try and do this, over and over again.

In the evolutionary old days, new and richly interpretable information was relatively scarce. Now we’re swimming in it, and getting it on our phones to alleviate the opioid deprivation of waiting in line. But we still act like it’s scarce, and seek out that next hit, because we can’t help ourselves; it’s how we’re built. Scarcity is a powerful motivator. Biederman calls us infovores.

I had read about this study from secondhand sources but seeing actual presentation materials from Biederman is 100x more fun. You can download the slides from his Central European University lectures here. You can also download the images used in the Scene Preference Study there. Flipping through them is sort of like a real-life version of The Parallax View montage.