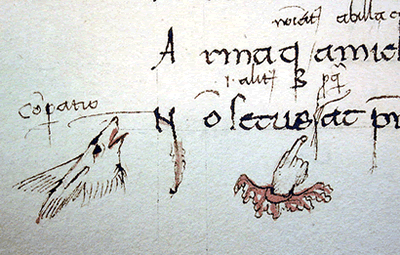

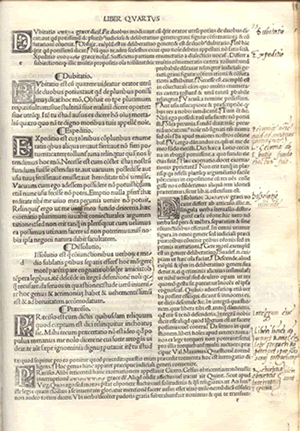

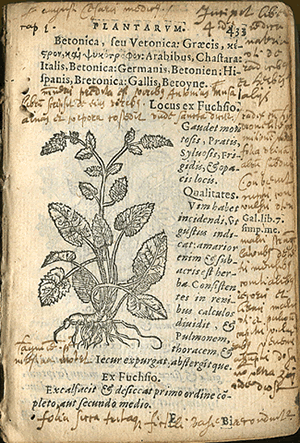

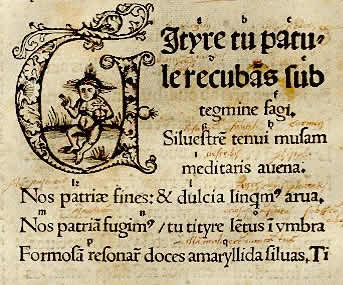

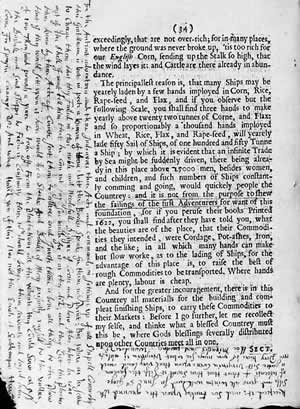

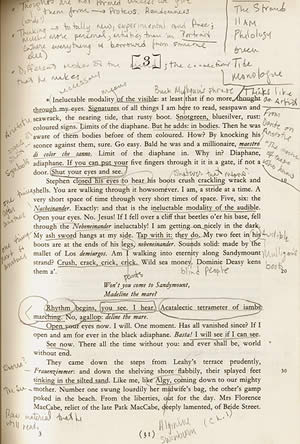

“In getting my books, I have been always solicitous of an ample margin; this not so much through any love of the thing in itself, however agreeable, as for the facility it affords me of pencilling suggested thoughts, agreements, and differences of opinion, or brief critical comments in general. Where what I have to note is too much to be included within the narrow limits of a margin, I commit it to a slip of paper, and deposit it between the leaves; taking care to secure it by an imperceptible portion of gum tragacanth paste.”

Edgar Allan Poe, 1884

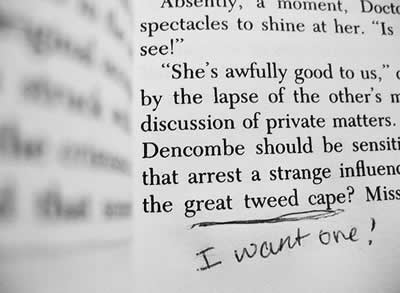

While I’m on the marginalia beat, let’s take a quick tour of glosses past and present.

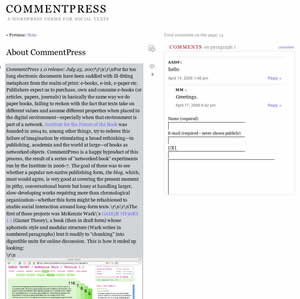

People have actually been trying to get annotation right on the web for over a decade—see Diigo, SharedCopy, A.nnotate, Trailfire, ShiftSpace (“an open source layer above any webpage” from NYU’s ITP) and many others. But the tool that comes closest to enabling the freeform marginalia of olde is the one that doesn’t try to at all: Twiddla. An all-out hit at the April NY Tech Meetup (and some web conference in Texas), Twiddla’s a completely web-based “team whiteboarding” app ideal for marking up and defacing web pages. Try it out in their sandbox.

For a detailed history of marginalia, check out this book by H. J. Jackson.